Here are some examples of work by architects which display a fictive premise or tendency.

Let’s start with a building of my own which uses literal representation in a way which makes the architecture unambiguously fictive.

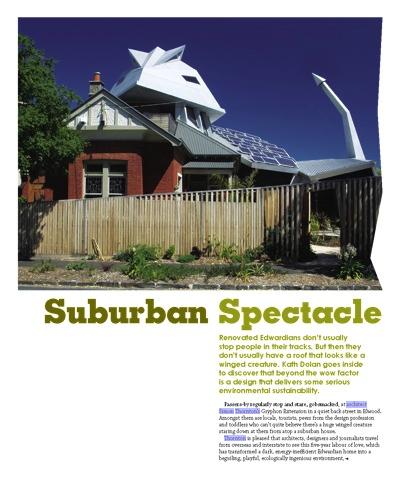

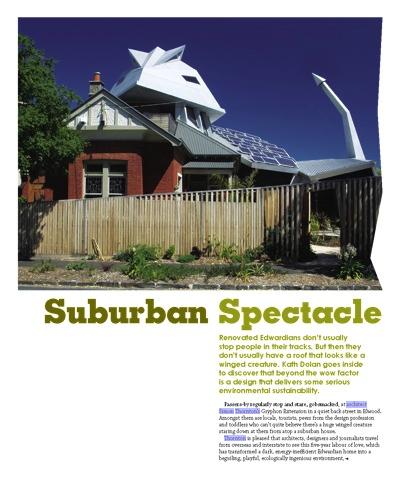

The Gryphon

The Gryphon (Photo: Andrew Griffiths/Lens Aloft )

The Gryphon (Photo: Andrew Griffiths/Lens Aloft )

The Gryphon, as it appeared in Green Magazine. (Photo: Tamsin O’Neill)

The Gryphon is an extension to an existing house in Elwood in Melbourne. The design is generated from a fiction narrative unconnected with the context or function of the building. The primary organising form is that of a mythical creature with the head and wings of an eagle and the hind quarters of a lion. In turning this form into a building, the language style of the Lockheed F-117A stealth fighter was appropriated.

Through this complex symbolic form it is possible to explore our understanding of the relationship between ‘earth’ and ‘sky’, and the moral imperative to guard what is precious. The interplay between our understanding of ‘house’ and our separate knowledge of the structure and form of ‘animal’ sets up an intellectual and emotional dialogue during exploration of the exterior and internal spaces.

The building also addresses our instinctive fear of large creatures, and may expose our repressed anxieties about our propensity to eat smaller creatures! Feelings more associated with relationships, such as fear and anxiety, as well as a sense of nurturing and fondness, are enabled by the formal likeness.

In the end each visitor, whether a child or adult, engages with the building from their own unique history of associations, and creates their own response.

Link: http://thorntonarchitecture.com/the%20gryphon%20extension.htm

The Melbourne Recital Centre

Melbourne Recital Centre (photo © Peter Glenane/Major Projects Victoria 2008) by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM)

Melbourne Recital Centre (photo © Peter Glenane/Major Projects Victoria 2008) by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM)

The Melbourne Recital Hall is a precious object isolated from the outside world. The literally-represented polystyrene foam and bubblewrap packing provokes the viewer to consider the wider implications of the relationship between a timeless, spirited performance, and the ‘throw away’ container. Permanence and transience, what remains, and what is left behind, become questions to ponder.

The implied motion of the partly-withdrawn white ‘packing’ is a playful deception – a fictive gesture within a non-fiction narrative.

The change of scale to ‘supersize’ is a also fictive aspect. As we enter the building we experience a converse Alice in Wonderland sense of having shrunk.

Definitely one of my favourites.

The Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance Visitor Centre

Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance Visitor Centre by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM) : view from top of Shrine to entry courtyard of Visitor Centre.

Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance Visitor Centre by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM) : view from top of Shrine to entry courtyard of Visitor Centre.

View of Shrine from within the crater seen above

View of Shrine from within the crater seen above

This project is also by Ashton Raggatt McDougall. The project incorporates a non-fiction narrative (including fictive re-enactments) derived from the purpose of the building. The top photo shows a fictive re-enactment of a shell or bomb crater adjacent to the original Shrine of Remembrance. This is repeated on the west side of the Shrine (not shown) and the two are linked with an underground chamber. This fictive spatial order echoes the architecture of the trenches and tunnels of war, and in so doing allows the visitor to connect with the reality of being there.

The Mornington Centre

The Mornington Centre by Lyons.

In his article ‘Surface fiction: Lyons Architecture practice profile’ (Monument #37 ) Brent Allpress writes ‘Lyons draw on a scenographic architectural tradition that can be traced back to the Picturesque movement of the eighteenth century. The picturesque image tended to efface its own artifice through an idealisation of ‘nature’ as a framed view. While Lyons also design more for the view than the plan, the fictive construction of the image is given overt prominence.’

http://www.architecture.rmit.edu.au/People/Allpress_Surface_Fiction.php

The Aqueduct and Tent House

In designing this house for a client who has spent most of her life running a die-casting factory with her late husband, I wanted to engage with engineering culture. It is hard to imagine a better example of the mind-set of the engineer than the construction of Roman aqueducts. Their approach seems to have been to connect the water source and destination by a straight line, at a slight descending angle, and not worrying about valleys and hills; they just ploughed right through them! Since the house site is very long and thin, I realised that the form of an aqueduct would fit well on the block, and if skewed to true north, would run from corner to corner. Hollowed out, it would serve as a passage, allowing rooms and external spaces of various sizes to be located alongside it. In the tradition of carpenter gothic, the ‘aqueduct’ is entirely constructed of wood, but the exposed radially-sawn hardwood weatherboads will turn a stony grey, giving the impression of weight.

Thinking about this weightiness reminded me of the book The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, where two ideas of existence are contrasted: Is a person’s action of no consequence and disappears into oblivion? Or should we act as if every action repeats heavily for all eternity, as Neitzche argued? This juxtaposition of lightness and heaviness suggested an architectural representation. As the aqueduct seemed to stand for repetition and heaviness, by contrast the rooms of the house could be in the form of tents – the lightest form of architecture. To refine the formal language of the house, I visited websites of contemporary Medieval pageants, and adopted the language style of the striped tents, and for the aqueduct part of the house, the aesthetic of the wooden battlements.

This house invites reflections on conception, birth, death, time, morality, belief and faith within a fiction narrative unconnected with the context or purpose of the building.

This gallery will be extended and updated.

Please send suggestions, photos and links to simonthornton@smartchat.net.au

Melbourne Recital Centre (photo © Peter Glenane/Major Projects Victoria 2008) by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM)

Melbourne Recital Centre (photo © Peter Glenane/Major Projects Victoria 2008) by Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM)