FICTION ARCHITECTURE

What is narrative in art, music, sculpture and architecture? It is the representation of an image, sound, shape or form which suggests a story. Narrative may be fictional or nonfictional. And it can be represented in all artistic styles from abstract through to highly realistic.

An example of narrative in music is ‘The Lark Ascending’ by Ralph Vaughn Williams. As the notes go higher and higher the imagination of the listener is able to picture a bird rising on thermal currents into the sky. I suspect that the music does not refer to any particular lark but rather to a fictional lark of the imagination. However if we listen to Steve Reich’s work ‘Different Trains’, he describes the narrative as documentary because it includes actual voice recordings of passengers.

An example of narrative in music is ‘The Lark Ascending’ by Ralph Vaughn Williams. As the notes go higher and higher the imagination of the listener is able to picture a bird rising on thermal currents into the sky. I suspect that the music does not refer to any particular lark but rather to a fictional lark of the imagination. However if we listen to Steve Reich’s work ‘Different Trains’, he describes the narrative as documentary because it includes actual voice recordings of passengers.

War artists, in this case Jules George, are entrusted with the task of recording actual scenes of battle. The narrative here is documentary, and the introduction of a fictional narrative would not be acceptable.

War artists, in this case Jules George, are entrusted with the task of recording actual scenes of battle. The narrative here is documentary, and the introduction of a fictional narrative would not be acceptable.

The portrait of Heath Ledger (2008) by Vincent Fantauzzo is a portrait and is therefore a nonfiction work. Interestingly he incorporates a fictional strategy of using two other viewpoints of Ledger to represent ‘voices’ which he hears in his head. This may be called ‘creative nonfiction’, which I will go into later.

The portrait of Heath Ledger (2008) by Vincent Fantauzzo is a portrait and is therefore a nonfiction work. Interestingly he incorporates a fictional strategy of using two other viewpoints of Ledger to represent ‘voices’ which he hears in his head. This may be called ‘creative nonfiction’, which I will go into later.

Next we will look at ‘The Weeping Woman’ by Picasso. We may not know why she is weeping but we feel sympathetic and are pulled into her story. This painting is a response to an actual situation, and so may be classified as having a nonfiction narrative.

Next we will look at ‘The Weeping Woman’ by Picasso. We may not know why she is weeping but we feel sympathetic and are pulled into her story. This painting is a response to an actual situation, and so may be classified as having a nonfiction narrative.

In sculpture there is a long tradition of representing nonfiction narrative, as in this lifelike representation of Admiral Lord Nelson.

In sculpture there is a long tradition of representing nonfiction narrative, as in this lifelike representation of Admiral Lord Nelson.

Sculpture can also contain a fictional narrative, such as this rat by British street artist Banksy. Notice that while all the components of this sculpture are nonfiction (the rat, the cap, the paint brush and the pack) they are brought together within a fictional narrative framework.

Sculpture can also contain a fictional narrative, such as this rat by British street artist Banksy. Notice that while all the components of this sculpture are nonfiction (the rat, the cap, the paint brush and the pack) they are brought together within a fictional narrative framework.

And in architecture we can find a good example of narrative in Charles Moore’s ‘Piazza d’Italia’, built in New Orleans in the mid nineteen seventies, where Roman arches and a map of Italy combine to tell a story about the Italian influence in the area’s cultural development.

And in architecture we can find a good example of narrative in Charles Moore’s ‘Piazza d’Italia’, built in New Orleans in the mid nineteen seventies, where Roman arches and a map of Italy combine to tell a story about the Italian influence in the area’s cultural development.

Narrative is not always a significant part of artistic expression, and even when it is present, it may be unacknowledged by the artist. In architecture most buildings show no clear expression of narrative. In the Piazza d’Italia however we see a rare example of architecture shaped by a narrative which is expressed in a highly literal way.

While narrative in literature may be nonfiction or fiction, narrative in architecture is almost always nonfiction. When starting to read a text in literature we are used to asking the question ‘Is this fiction, or is it factual?’ When entering a new building we just accept that this is the architect’s idea of how a building should be designed in order to be cost effective, ecologically sustainable, and watertight. Fiction does not enter into our thinking.

The Melbourne building called Council House 2 is a good example of this.

The Melbourne building called Council House 2 is a good example of this.

There is quite an overt narrative which is drawn from the function of the building. You can see how the various sustainable features have been expressed and made elegant, such as the vertical ventilation stacks. This building has a nonfiction narrative relating to sustainability which connects with a meta-narrative about global warming.

While some narratives spring from function, others spring from the purpose of the building. Again choosing the Piazza d’Italia, this narrative was generated by the desire to create an identifiable place around which a number of speculative office buildings would be developed.

The Italian theme was chosen primarily from the point of view of creating an identity for a commercial proposition in much the same way that Lucy the Elephant was built to attract people to a real estate development at Margate in New Jersey in 1881.

The Italian theme was chosen primarily from the point of view of creating an identity for a commercial proposition in much the same way that Lucy the Elephant was built to attract people to a real estate development at Margate in New Jersey in 1881.

However the elephant building is different in one respect: the elephant form is only a way of attracting attention. There isn’t anything about an elephant that says ‘real estate’

More common are buildings which have a visible form closely related to their purpose, such as the Tail o’ the Pup kiosk, or the coffee pot shape of Bob’s Java Jive.

More common are buildings which have a visible form closely related to their purpose, such as the Tail o’ the Pup kiosk, or the coffee pot shape of Bob’s Java Jive.

This type of building was most common in California in the 1920’s and 1930’s when there were literally hundreds built to attract attention from passing traffic.

They have been lovingly documented in Jim Heimann’s book ‘California Crazy and Beyond’.

They have been lovingly documented in Jim Heimann’s book ‘California Crazy and Beyond’.

Australia has a number of such buildings, most famously the Big Pineapple.

Australia has a number of such buildings, most famously the Big Pineapple.

In recent times there have been a number of quite extravagant commercial buildings advertising their wares, as in the case of the headquarters of the Longaberger Basket company.

In recent times there have been a number of quite extravagant commercial buildings advertising their wares, as in the case of the headquarters of the Longaberger Basket company.

Some, like Lucy the Elephant, have no apparent connection between form and purpose. An example is the New York New York hotel and casino in Las Vegas, which replicates iconic New York buildings simply to create a spectacle.

Some, like Lucy the Elephant, have no apparent connection between form and purpose. An example is the New York New York hotel and casino in Las Vegas, which replicates iconic New York buildings simply to create a spectacle.

So far we have dealt with narratives generated by function and purpose, and now I would like to introduce a third category: context.

A building near mountains may be shaped to echo the mountains (architect Robyn Boyd in this case); a building near red brick buildings may be constructed also of red bricks; an infill house in a street of three storey terrace houses may respond to context by also being three stories high.

A building near mountains may be shaped to echo the mountains (architect Robyn Boyd in this case); a building near red brick buildings may be constructed also of red bricks; an infill house in a street of three storey terrace houses may respond to context by also being three stories high.

A Hollywood starlet who built her house on the beach in the shape of a ship and lighthouse has certainly adopted a narrative approach to context.

A Hollywood starlet who built her house on the beach in the shape of a ship and lighthouse has certainly adopted a narrative approach to context.

And this building designed in Hollywood to look like a house where a witch in the story of Hansel and Gretel might live is a good example of a narrative response to cultural context because of the nature of the film industry in the vicinity.

And this building designed in Hollywood to look like a house where a witch in the story of Hansel and Gretel might live is a good example of a narrative response to cultural context because of the nature of the film industry in the vicinity.

The Gagadju Crocodile Holiday Inn in Australia, which appears from the air to be a giant crocodile, is responding to the Aboriginal cultural and ecological context.

The Gagadju Crocodile Holiday Inn in Australia, which appears from the air to be a giant crocodile, is responding to the Aboriginal cultural and ecological context.

A building with a narrative which responds to context is nonfiction because it ‘comments’ on the actual circumstances which surround it, illuminating the context in some way.

It seems surprising that fictive ideas generated by the function, purpose or context of buildings can exist in buildings which have nonfiction ‘narrative frameworks’. However if we compare architecture with literature we can draw an analogy here with the work of Lee Gutkind and his concept of creative nonfiction writing. Even though a topic is nonfiction it can still be explored using all kinds of fictive proposals and re-enactments. For example the nonfiction genre of biography can contain a fair degree of fictive speculation and dot-joining. Another analogy is that of the advertising industry, which often uses fictional scenarios within the nonfiction framework of the advertisement. When we look at a hot dog shaped building selling hot dogs we are looking at the same thing: a fictional narrative (Let’s pretend this building is a hot dog!) subordinated to a nonfiction narrative framework (‘We sell hot dogs’).

Everywhere we look we find that fictive narratives are subordinated to the main paradigm in architecture, which is nonfiction. And despite the fact that we architects enjoy these kinds of structures, which we label ‘programmatic buildings’, we tend to look down on them because they are a popular culture phenomenon, and retreat to the safe ground of ‘high architecture’. How can we escape this entrapment in the nonfiction paradigm? And how can we elevate the status of literally represented narrative ideas in architecture so that programmatic buildings of all kinds are given the respect they deserve?

First it is necessary to accept the analysis set out in the arguments I have made: that virtually all current architecture is nonfiction even when it contains fictive narratives. Second, lessons must be drawn from the history of literature, specifically from the birth of the novel, which I am about to discuss. Third, there needs to be a paradigm shift to allow a new architectural category which, like the novel, is based on pretence, and in which fiction narratives have free rein according to the architects’ imaginings.

Prior to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders, English language fiction prose comprised forms such as folk tales, the texts of plays, short stories, and translations of picaresque works such as the Decameron and Don Quixote. Initially the novel was a kind of hoax. Defoe’s novels were not published under his name, but purported to be ‘true accounts’ of his heroes. Naturally the readers understood that this was tongue-in-cheek: they knew they were dealing with pretence, not a documentary account. From this analogy, it is possible to propose the birth of a category in architecture which can be called ‘fiction architecture’ where make believe narratives can have free rein, freed from merely being responses to function, purpose or context. Like books, buildings can then be classified as fiction architecture or nonfiction architecture.

Prior to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders, English language fiction prose comprised forms such as folk tales, the texts of plays, short stories, and translations of picaresque works such as the Decameron and Don Quixote. Initially the novel was a kind of hoax. Defoe’s novels were not published under his name, but purported to be ‘true accounts’ of his heroes. Naturally the readers understood that this was tongue-in-cheek: they knew they were dealing with pretence, not a documentary account. From this analogy, it is possible to propose the birth of a category in architecture which can be called ‘fiction architecture’ where make believe narratives can have free rein, freed from merely being responses to function, purpose or context. Like books, buildings can then be classified as fiction architecture or nonfiction architecture.

Architecture is 300 years behind literature: it has a lot of catching up to do, in my opinion.

What, then, does fiction architecture look like? And I am not talking about futuristic drawings or descriptions of buildings, which is architectural fiction. In ‘fiction architecture’ the ideas are expessed through the fabric of the building for the contemplation of occupants and visitors.

FIVE EXAMPLES OF FICTION ARCHITECTURE

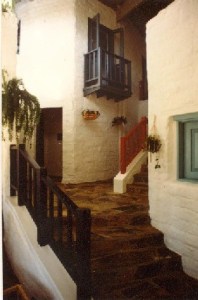

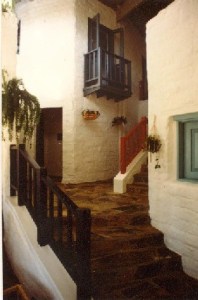

The Greek Village House

The first example I will show from my own work goes back to 1985 and is called the Greek Village House. The owners had bought a block of land near Macedon, a small town about an hour’s drive north-west of Melbourne in Victoria. There were a number of stipulations from the owners including lots of winter sun and mud brick walls throughout. I was troubled at the time by the notion that international holiday travel was only one step away from colonialism because tourist invaders would cheerfully plunder photographs without compensation and carry them off to their home lands.

As it happened the owners of the block of land had a wonderful collection of photographs of streets and houses on Greek islands which they had taken on a recent holiday. In what may be interpreted as a further act of plundering I was seized with the urge to recreate one of the photos as closely as possible, as the interior hall and stairway of the house.

As it happened the owners of the block of land had a wonderful collection of photographs of streets and houses on Greek islands which they had taken on a recent holiday. In what may be interpreted as a further act of plundering I was seized with the urge to recreate one of the photos as closely as possible, as the interior hall and stairway of the house.

Working in plan, I recreated the street in the photo and adapted the houses to each become a room in the new house. The plan grew like the plan of a village might grow over time as each house is built. I set this plan under a large tent-like roof which radiated from the centre of the plan, enabling the parapet roofs in the original photo to be expressed. What results is a piece of fiction architecture on the theme of tourism. Like a novel it deals with ideas and issues but does not necessarily put forward any particular line of argument. The owners, their guest and visitors were left to contemplate their own opinions within a narrative of make believe. The shower recess even has a map of the Greek islands made of tiles.

Working in plan, I recreated the street in the photo and adapted the houses to each become a room in the new house. The plan grew like the plan of a village might grow over time as each house is built. I set this plan under a large tent-like roof which radiated from the centre of the plan, enabling the parapet roofs in the original photo to be expressed. What results is a piece of fiction architecture on the theme of tourism. Like a novel it deals with ideas and issues but does not necessarily put forward any particular line of argument. The owners, their guest and visitors were left to contemplate their own opinions within a narrative of make believe. The shower recess even has a map of the Greek islands made of tiles.

The Lighthouse

The second example is The Lighthouse. Not far from the Greek Village house rises Mt.Macedon and I was struck by the way it appeared like an island set in a sea of land. The site was badly located for winter sun and I wanted to use a giant periscope to pull sunshine down onto the land. A vague memory of reading an article by a feminist artist about nineteenth century objects in the landscape and how they were often innately phallic and implicitly patriarchal must have assisted at this point in helping me form the idea that the house could be a lighthouse in reverse, where light entered at the top and was reflected down into the rooms below. Reponse to context was important in all this but my idea transcended this consideration and took flight the moment that make believe entered the picture.

Not content to represent a generic lighthouse I began a process of looking at books on lighthouses and chose one to copy. It was a very small lighthouse and I had to make it quite a bit bigger in order to fit rooms into it.

Not content to represent a generic lighthouse I began a process of looking at books on lighthouses and chose one to copy. It was a very small lighthouse and I had to make it quite a bit bigger in order to fit rooms into it.

I drew a sketch plan to show the owners Bruce and Alison, and they accepted the concept.

I drew a sketch plan to show the owners Bruce and Alison, and they accepted the concept.

I was fortunate that Dr.Mirjana Lozanovska, who has completed a Ph.D study of the relationship between architecture and feminism, was working in our office at the time. She suggested that the Age of Enlightenment was a dark age for feminism. Rousseau’s views about the education of Emile differed greatly from his ideas about the upbringing of Sophie.

The design explores phallocentricity from the time of Plato through to the current period of feminist critique. The notion of the centrality of patriarchy under the scrutiny of feminism is represented by the lighthouse form under the gaze of the cottage windows, where the cottage represents the site of female economic power, prior to the rise of industrialised manufacture. The place between the cottages and the lighthouse tower is a village green with a pump, a now defunct female public realm where women communicated and exercised collective power in the village.

The lighthouse tower, where normally the light of male knowledge is ejaculated into the world, in this case functions in the opposite way to receive the sun’s rays and reflect them downwards into a ‘Plato’s Cave’ Living room where the fireplace and television are located. This could signify the possibility of an egalitarian concept of enlightenment, rather than one which is the preserve of ‘enlightened’ males who have climbed the stairway to the panorama above. The Lighthouse, appearing in the landscape as if it were an emblem of patriarchy, is actually a critique rather than an affirmation.

From all this it is clear that once a fictional starting point is adopted in architecture a great deal can unfold.

The Lighthouse at Mt.Macedon can be seen as a successor to the tugboat and lighthouse home in Los Angeles shown earlier, but with a narrative freed from merely reflecting context.

The Gryphon house extension

The third example is The Gryphon. This house extension looms over an existing red brick Edwardian house in the Melbourne seaside suburb of Elwood.

The owners Claire and Mark wanted something fanciful to make a lovely place for foster children and their only indication of the aesthetics was to say that they liked Antonio Gaudi’s work. My father became terminally ill in England and I travelled there to be with him and attend his funeral. I had a chance to visit the Casa Mila, the Casa Battlo and the Parc Guell, and found them to be deeply serious and beautiful. Some time after returning to Australia I awoke in the middle of the night and drew an image of a birds head towering over the house.

The owners Claire and Mark wanted something fanciful to make a lovely place for foster children and their only indication of the aesthetics was to say that they liked Antonio Gaudi’s work. My father became terminally ill in England and I travelled there to be with him and attend his funeral. I had a chance to visit the Casa Mila, the Casa Battlo and the Parc Guell, and found them to be deeply serious and beautiful. Some time after returning to Australia I awoke in the middle of the night and drew an image of a birds head towering over the house.

I also drew a plan and elevation, then went back to sleep. Claire and Mark responded with excitement and this fictional narrative took flight, transforming itself into a mythical beast.

There are many precedents for buildings shaped like animals such as the Big Duck poultry shop in California.

There are many precedents for buildings shaped like animals such as the Big Duck poultry shop in California.

In Australia there is the Big Merino and the Giant Koala. While these precedents have narratives constrained by their commercial nonfiction purpose, the Gryphon narrative has free rein.

In Australia there is the Big Merino and the Giant Koala. While these precedents have narratives constrained by their commercial nonfiction purpose, the Gryphon narrative has free rein.

The Milk Carton house extension

The fourth example of fiction architecture is a house extension in the Melbourne inner city suburb of Brunswick. The extension is on the side of an existing Edwardian weatherboard house. The owners Jen and Neil wanted a two storey building with bathroom and toilet downstairs and a studio upstairs. I was given no directions on aesthetics but I could not help noticing that these people had ‘attitude’. I wondered if this was the place to do something I had always wanted to do: build a house in the shape of a food package. The footprint sort of fitted, and the height was okay for a Tetra Pak as long as it was chopped a third the way up the carton. I made a model using a real milk carton, cutting out windows and folding up sunshades.

Everything was immediately right, even the graphics on the carton, which mentioned such contentious words as ‘pure’, ‘unhomogenised’ and ‘low fat’. And because milk is white, there was no shortage of symbolism to be grappled with. I particularly liked the way this object came directly from our own kitchen table and seemed to say a lot about the puritanical times we live in.

The Milk Carton can be compared to several commercial milk kiosks in the shape of milk bottles. This example is the Benwah Milk Bottle building in Spokane, Washington. By contrast with the Milk Carton, this milk bottle is tied closely to the nonfiction narrative of an advertising strategy.

The Milk Carton can be compared to several commercial milk kiosks in the shape of milk bottles. This example is the Benwah Milk Bottle building in Spokane, Washington. By contrast with the Milk Carton, this milk bottle is tied closely to the nonfiction narrative of an advertising strategy.

The Rocket House

The fifth and final example is the Rocket House. Designed for Bruce and Alison as a retirement home after they moved from the Lighthouse to a more gently sloping block further west at Woodend, it was an opportunity to follow another fictional narrative which I have been interested in for a long time. A spaceship or some other kind of large rocket appears to have crashed into the hillside and then has been occupied and converted to a dwelling.

Visitors to the house have to ponder how it could have happened and what it signifies. I am happy for multiple interpretations to emerge. Perhaps the owners are aliens, or perhaps the survivors of a failed expedition to Mars. Personally I get satisfaction from the idea that the crashed rocket might represent the ‘coming down to earth’ of mid twentieth century ambitions to conquer the universe, and the realization that there are limits to growth and the use of resources.

CONCLUSION

The five projects shown demonstrate that architecture incorporating fiction narratives can be achieved, beyond the constraints of function, purpose and context. Within a fictional narrative framework, ideas may be developed and expressed freely, as occurs in the form of the novel in literature.

PHOTO CREDITS

Picture of lark ascending

https://jahnavi.files.wordpress.com/2006/12/b0106800_2075826.jpg

Jules George Afganistan war picture

http://digitalproductionme.com//pictures/Green%20smoke%20of%20Shawqat.jpg

Heath Ledger

http://www.vincentfantauzzo.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/portrait_heath_archibald_prize_2008_artist_vincent_fantauzzo_850.jpg

Picasso ‘The Weeping Woman’

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/T/T05/T05010_10.jpg

Admiral Lord Nelson

http://www.beautifulengland.net/photos/var/resizes/london/trafalgarsquare/admiralhorationelsonontopofhiscolumntrafalgarsquare2.jpg?m=1376332341

Banksy Bronze Rat

http://www.postersandprintsblog.com/storage/banksy%20bronze%20rat.jpg?__SQUARESPACE_CACHEVERSION=1317043980584

Piazza d’Italia (a)

https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/157/385935112_4057335dfc.jpg

Council house 2

http://cdn3.greendiary.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ch2-melbourne-oz-council-house-2-ch2-melbourne-1.jpg

Piazza d’italia (b)

http://ad009cdnb.archdaily.net.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/1304516017-gail-des-jardin-1000×664.jpg

Lucy the elephant

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/b/b0/Lucy2011.JPG/250px-Lucy2011.JPG

Tail o’ the pup

http://www.roadsideamerica.com/attract/images/ca/CALAStailopup_falk.jpg

Bob’s Java Jive

https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRi5a7sP7Zt8eKUCju_dBc3eJxLGqfYTxSmRGDqhu2u3FTeO7uCFg

The Big Pineapple

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/travel/news/police-investigate-big-pineapple-sabotage/story-e6frg8ro-1226398260657&h=421&w=316&tbnid=3gbUr6qnjJgtlM:&zoom=1&docid=IiwSED1YTBpAfM&ei=j6AUVaikCcPy8QWK3IC4Aw&tbm=isch&ved=0CDwQMygLMAs

The Big Basket (Longaberger Company Headquarters)

http://chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/files/2011/07/2010041310280162.jpg

New York New York Hotel and Casinos, Las Vegas

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Las_Vegas_NY_NY_Hotel.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Las_Vegas_NY_NY_Hotel.jpg

Tower Hill Reserve Visitor Centre, Tower Hill, Victoria by Robin Boyd

https://c2.staticflickr.com/6/5291/5451367373_4689119889_b.jpg

Irvin Willat Studio (Hansel and Gretel witch’s house) by motion picture designer Harry Oliver, 1921

https://fictionarchitecture.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/7f232-dsc_0199.jpg

Gagudju Crocodile Holiday Inn, Jabiru

http://resources2.news.com.au/images/2014/07/02/1226975/356482-0312e876-01a9-11e4-8a13-c9890f82f8cd.jpg

Creative Nonfiction Magazine, Pittsburg, founded by Lee Gutkind in 1993

http://bulletin.swarthmore.edu/sites/bulletin.swarthmore.edu/files/assets/Winter15/BookReviewTHUMB.jpg

Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe, London, 1720

http://www.jahsonic.com/RobinsonCrusoe.jpg

Photos of the Greek Village house by Simon Thornton

Photos of the Lighthouse by Simon Thornton

Trancas Beach Tugboat and Lighthouse dwelling, Los Angeles

Illustrated in Jim Heimann, California Crazy and Beyond: roadside vernacular architecture, 2nd ed. San Francisco, 2001, 41

Photos of the Gryphon house extension by Simon Thornton and John Gollings

The Big Duck, Long Island

https://encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQjkl-GYLyniwceNl-4YTAUuITlhegVn_x0PjAki40baRkXiM0M

The Giant Koala, Dadswell Bridge, Victoria, Australia

https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQ3zJvvTz3IIsIpcTITXewigJ72aEYFB98okN-33qJ04ykK-wn2

The Big Merino, Goulburn, New South Wales, Australia

https://encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTD3dwzslHLKfdyyDYWtNb5BZ8pAVl6RTIjeaeUAXj_ca5gYQniOg

Photos of the Milk Carton house extension by Simon Thornton, Mark Munro and Neil Davis

Milk Bottle Kiosk, Spokane, Washington

http://www.turnipmoney.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/milk.jpg

Photos of the Rocket House by Simon Thornton

This paper was presented to the National Convention of the Popular Culture and American Culture Associations at New Orleans on April 3 2015. This is a slightly revised version dated 14th April 2015.

Copyright Simon Thornton 2015.

Contact the author at simonthornton@smartchat.net.au

Simon Thornton is a director of Simon and Freda Thornton P/L Architects in Alphington, Melbourne, Victoria 3078, Australia.